Key Takeaways:

- Comprehensive tax and estate planning guidance is critical to the success of a business transition plan

- Correct choice of techniques can maximize tax efficiency while also achieving the family's other important goals

- Strategies that "freeze" the value of a business for estate and gift tax purposes can be particularly effective

A family business transition to a second generation, or other family members, has always been a popular business succession plan for obvious reasons. When you spend so much time and effort building a successful enterprise, you may feel more comfortable dealing with new owners who sharing your values, experiences and beliefs – a very important consideration in any succession plan.

However, it is important to note that a succession plan based on a family business transition to a second generation involves a whole host of tax and estate planning issues that can differ from those surrounding a sale to a third party. This article will discuss some of the most common issues that arise with intra-family succession planning and some strategies that can be employed to address them.

Gift and Transfer Taxes

Special attention must be paid to issues of transfer tax (gift, estate and generation-skipping transfer taxes) in any transaction involving a family member. In 2022, under US tax law, individuals1 can gift up to $16,000 to as many people as they wish, annually, without incurring gift tax. This is called the gift tax annual exclusion.

In addition, individuals also have a lifetime gift tax exemption of $12.06 million. Any transfers that exceed the lifetime exemption amount will be subject to a tax rate of 40%.2 Transfers to family members that are not a bona fide sale for fair market value may be counted as gifts and force the transferor to expend their gift tax exemption amounts. Many businesses have fair market values that far exceed the current gift tax exemption amounts, so their owners often employ various strategies to carry out intra-family transfers while being mindful of such transfer tax rules.

Transferring a business to family members, particularly if growth is expected for the business, is a powerful planning technique because it may serve to “freeze” the value of the business at its current value for estate tax purposes. The idea being that, if an asset expected to appreciate in value is transferred to family members prior to such appreciation, then that growth and appreciation in asset value would take place outside of the business owner’s estate and potentially save a large amount of transfer tax. This “value freeze” planning may be accomplished through several different techniques.

Installment Sales and Intra-Family Loans

A very basic technique often employed to support a family business transition to a second generation is an installment sale, coupled with an intrafamily loan. On a basic level, this involves selling a business to a family member using a loan, documented by a promissory note payable over time. Several important tax rules are implicated in such transactions.

Any owner selling a business to a family member would need to substantiate the sale price. For such a related-party transaction, the IRS will not simply allow the buyer and seller of a business to negotiate any price they wish. The situation could lead to abuse, such as an owner selling a multimillion-dollar enterprise to their child for only $1. In this type of related-party transaction, the business owner will need to employ a qualified third-party valuation professional to conduct a valuation of the business. This process substantiates the company’s value for the sale.

The valuation requirement also provides a potential planning opportunity. The shares of a closely-held business may be eligible for valuation discounts due to lack of control and/or lack of marketability. In particular, shares subject to restrictions under a shareholder agreement, may be eligible for such discounts. A valuation expert may be able to substantiate this basis for a discount in their report. Such a valuation discount may reduce the overall cost to the family-member borrowers of the transaction.

Additionally, a minimum rate of interest must be charged on any loan associated with such a transaction. A loan to a family member that does not satisfy the IRS minimum interest rate requirements risks being counted by the IRS as a gift, thus expending the lender’s gift tax exemption and potentially incurring gift tax.

The IRS publishes their required minimum interest rates – referred to as the Applicable Federal Rate (AFR) – on a monthly basis, with different rates assigned based on the term of a loan. In January 2022, for example, the AFR in effect for loans with maturities between three and nine years is 1.30%, and for loans with maturities of more than nine years, the AFR is 1.82%. Low AFRs, such as those currently in effect, make intrafamily loans a very attractive option. However, it is also important to note that interest paid on the loan will be taxable income to the “lender” (in our case, the business owner) as ordinary income.

The mechanics of such an installment sale to a family member using an intrafamily loan offer several advantages. By structuring the deal as an installment sale, the business owner can spread out the realization of capital gains on the transaction over multiple tax years to provide some deferral.

As long as the IRS AFR requirements are satisfied, the parties have some flexibility in terms of structuring the loan payments associated with the sale. There is room to account for expected cash flow from the company, and any cash flow needs of the business owner after the transition is complete.

It is crucial to recognize that the loan and promissory note associated with such an intrafamily sales transaction create genuine legal obligations, and thus, the purchasing family members must be prepared to meet all of their obligations under the loan. That includes keeping payments up to date.

The parties should also be prepared to have an “exit strategy,” particularly if the selling business owner may pass away prior to the note being fully paid. Several options exist, including strategies involving life insurance on the seller to provide additional liquidity for the borrowing family members. This additional liquidity could be particularly useful as a source of collateral if, for example, the borrower needs to refinance the family loan with a third-party lender after the seller’s death.

In a transaction of the type outlined above, the value of the promissory note would still be included in the deceased business owner’s estate for transfer tax purposes.

Self Cancelling Installment Note

One option that some families leverage to make an installment sale and intra-family loan transaction more effective for estate planning purposes is a promissory note. Specifically, this document contains a special provision canceling any unpaid balance on the loan in the event of the lender’s death.

Such a promissory note is referred to as a Self-Canceling Installment Note (SCIN). This technique provides advantages for estate tax planning because it prevents the unpaid balance of a promissory note from being included in the lender’s estate at death (thus potentially providing a significant estate tax savings). As one would expect, the SCIN technique is not appropriate for every situation and must follow strict requirements, or the IRS may challenge the technique.

The SCIN tactic is most suitable in a situation where a lender, such as a company owner planning a family business transition to a second generation, would potentially fail to survive the full term of the loan. In many other cases, the SCIN would not provide any advantage over a normal promissory note. Furthermore, the seller must retain no control over the asset (such as a business) being sold in such a transaction. The self-cancelation provision of a SCIN must additionally be bargained for as part of the consideration for the sale (which should be carefully documented by the parties and their attorneys).

An important distinction with a SCIN transaction is that there must be a “risk premium” paid to the seller. This premium may either be reflected by a higher-than-market value price paid by the buyer, or the note back to the buyer should carry an above-market interest rate. This “risk premium” is necessary in order to establish an arm’s length transaction between the buyer and seller.

The computation of such risk premiums is a complex analysis involving actuarial data regarding the lender’s life expectancy, along with analysis computing a reasonable risk premium. Thus, SCIN transactions require careful consultation with not only attorneys and accountants, but also valuation and actuarial professionals who are highly experienced with such situations. While it certainly adds additional complexity to transactions, the SCIN technique can be a powerful tool for leveraging a client’s gift and estate tax exemptions. It remains a viable technique in the right circumstances.

Sale to an Intentionally Defective Grantor Trust

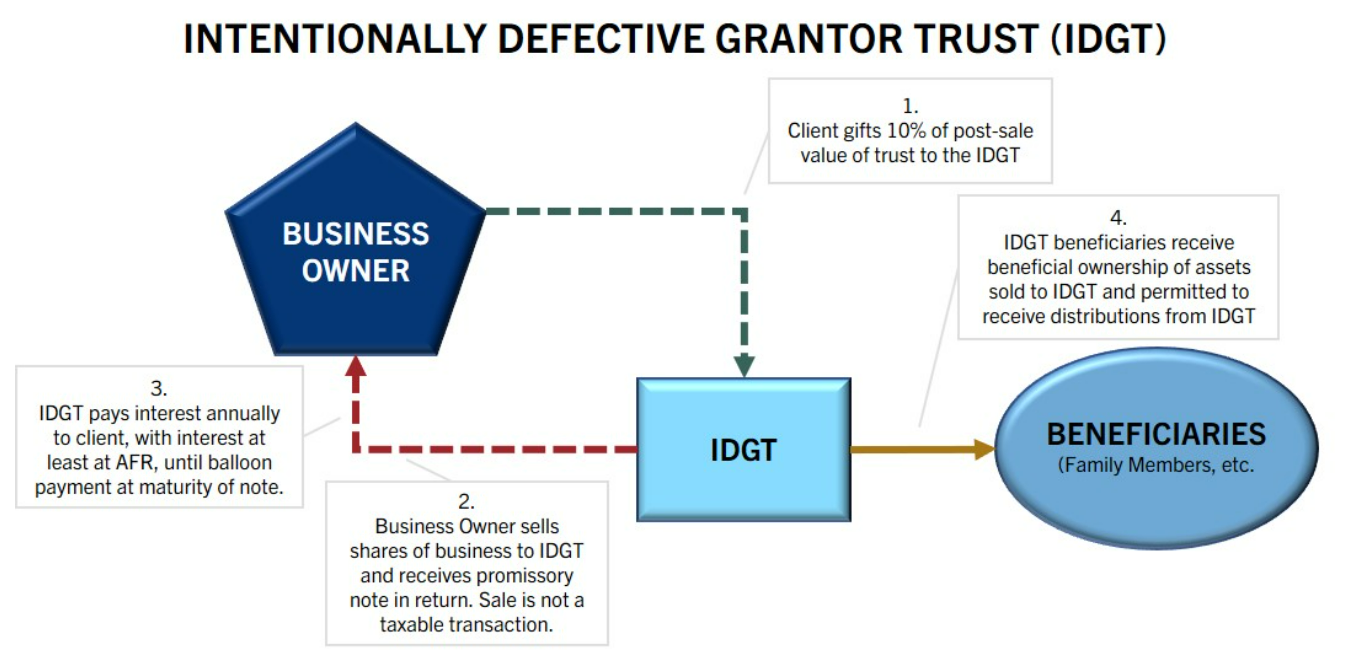

The use of an intentionally defective grantor trust (IDGT) is another powerful way for many business owners to further leverage an installment sale as part of a business succession plan.

An IDGT is a trust that is extremely efficient for such purposes. Not only is it effective for removing an asset from a grantor’s estate for transfer tax purposes, but it also has income tax benefits.

For example, the trust would be specially drafted so that the grantor remains responsible for the income tax liabilities of the trust. This allows the transfer to avoid being diluted by future income tax while the grantor is alive. This differential treatment is accomplished by drafting the trust to include certain powers (the most commonly seen being a power for the grantor to substitute assets in the trust) which under the Internal Revenue Code serve to render the grantor responsible for the income tax liabilities of the trust, regardless of whether the trust is effective for removing assets from the grantor’s estate.

Such different treatments under income tax versus transfer tax rules create several important advantages for the IDGT. For instance, the grantor of the trust – in this case, a business owner selling a business to an IDGT trust that benefits the owner’s family members – has an opportunity to leverage the value of the original gift by paying the trust’s income tax liability. Additionally, due to the grantor status of an IDGT, when a grantor/business owner enters into a transaction to sell their business to such a trust, there would be no capital gain recognized for the grantor on such a sale. The transaction between the grantor/business owner and the grantor trust would be disregarded. This potential to prevent a capital gains realization event, while still moving an asset into the IDGT trust and accomplishing an asset “value freeze,” provides a powerful opportunity for potential tax savings.

Movement of assets into an IDGT can be accomplished through gifting the assets to the trust, selling the assets to the trust, or a combination of both. In the next section, we will focus on one of the most commonly-used techniques, which involves the sale of a business to an IDGT.

In structuring any such sale of a business to an IDGT, the grantor will typically first establish the trust, and then provide a “seed gift", typically equal to 10% of the expected post-sale value of the trust. This helps to establish that the trust would be a “credit-worthy” borrower if viewed in terms of an arm’s length transaction, which is important if the IRS is to respect the bona fide nature of the sale transaction rather than considering it a gift.

The remainder of the business would then be sold to the IDGT as part of an installment sale, with the requirements regarding valuation and minimum rates of interest previously discussed in this article still applying to such a transaction when structured to include an IDGT. The previously discussed opportunities for valuation discounts may also be used to further leverage the power of a sale to an IDGT.

As of the date of this article, tax legislation has been proposed in Congress that could change the tax treatment of grantor trusts (including IDGTs) dramatically. The proposed legislation, if enacted, would eliminate the use of the IDGT strategy described above through provisions:

- Causing the assets of any grantor trust to be included in the grantor’s estate for transfer tax purposes.

- Deeming the sale of any asset to a grantor trust to be a taxable event for the grantor, requiring the recognition of capital gains in association with any such sale.

Any grantor trusts formed after the enactment of such legislation would fall under the new less favorable rules.

Flexibility

Flexibility is a key aspect of any plan for a family business transition to a second generation.

As the future cannot be predicted, it is important for a business owner to have contingency plans regarding succession planning, and to avoid creating structures that would be too inflexible and serve to tie their family members’ hands. The nature and profitability of the business, as well as the willingness of family members to work in the company, may all change over time. Every business owner must ensure that their plan can adapt to such changes.

Moving Forward with Your Business Transition

In this article, we have discussed some of the personal planning aspects of a business succession plan, including some of the most commonly encountered techniques for structuring such transactions. The techniques discussed in their article are far from exclusive, but do serve to give a broad overview of some of the most popular planning structures and techniques for business succession.

Open communication between business owners, their professional advisors, and their overall planning team is essential for the successful implementation of any succession plan. We hope that this article will help to facilitate the development of a strategy for keeping your business in your family’s hands.

1For purposes of this article, we are assuming that individuals discussed are US citizen taxpayers; different exemption amounts for non-US persons may apply, and all persons should carefully consult with their attorneys and tax advisers regarding their particular exemption amounts for planning purposes before taking any action or engaging in any strategies.

2Please note that the annual and lifetime exemption amounts are subject to change from year to year and, as of 2022, exemption amounts, and the tax rate, are subject to current proposed tax legislation that may dramatically alter the exemption amounts.

NOTE: IMPORTANT INFORMATION

Comerica Wealth Management consists of various divisions and affiliates of Comerica Bank, including Comerica Bank & Trust, N.A. and Comerica Insurance Services, Inc. and its affiliated insurance agencies. Non-deposit Investment products offered by Comerica and its affiliates are not insured by the FDIC, are not deposits or other obligations of or guaranteed by Comerica Bank or any of its affiliates, and are subject to investment risks, including possible loss of the principal invested. Comerica Bank and its affiliates do not provide tax or legal advice. Please consult with your tax and legal advisors regarding your specific situation.

This is not a complete analysis of every material fact regarding any company, industry or security. The information and materials herein have been obtained from sources we consider to be reliable, but Comerica Wealth Management does not warrant, or guarantee, its completeness or accuracy. Materials prepared by Comerica Wealth Management personnel are based on public information. Facts and views presented in this material have not been reviewed by, and may not reflect information known to, professionals in other business areas of Comerica Wealth Management, including investment banking personnel.

The views expressed are those of the author at the time of writing and are subject to change without notice. We do not assume any liability for losses that may result from the reliance by any person upon any such information or opinions. This material has been distributed for general educational/informational purposes only and should not be considered as investment advice or a recommendation for any particular security, strategy or investment product, or as personalized investment advice.